Fifty years ago, on June 25, 1965, a Bogalusa civil rights leader filed a lawsuit against city law enforcement.

When police were refusing to protect civil rights activists who were under threat in Bogalusa, another group -- the Deacons for Defense -- drew a line: "if you shoot at us, we will return fire."

Three civil rights workers had recently been killed in Mississippi, and Ronnie Moore and Mike Lesser were driving from Jonesboro to Monroe, Louisiana, when three cars surrounded them. As Moore remembers it, there were white men in the cars and he knew they were in danger.

They slammed on the brakes, made a u-turn and drove head first at the two cars trailing them.

"There was silence in the car, like, we are not going to die out here without taking one carload of crackers with us," Moore says. "That was the attitude. It was really tense. The two carloads split and we went right between them."

At the time, Moore was working as field secretary for the Congress of Racial Equality. CORE sent people to Jonesboro, among other places, to help organize voter registration drives, sit-ins and rallies. Moore and Lesser eventually got to Monroe that night, but they weren't driving alone.

"Many local guys came out with their guns and whatnot, and they escorted us," Moore says. "That was the beginning of their commitment to protecting the civil rights workers."

The Deacons for Defense, an armed self-defense organization, went against the principles of non-violence, patrolling neighborhoods and guarding homes. Martin Luther King refused to visit some communities where the Deacons were known to be active.

Charlie White was one of the group's founding members. White says CORE was reluctant to accept their help.

"They wanted help, but they didn't want to really depend on a violent organization," White says. "We [the Deacons for Defense] wasn't violent. We were just doing what we needed to do. When they accepted us, then they really started getting some things done."

The Deacons ultimately won over some of the CORE workers because of what law enforcement was doing to them. "Put them in jail, beat 'em up, those kinds of things," White says.

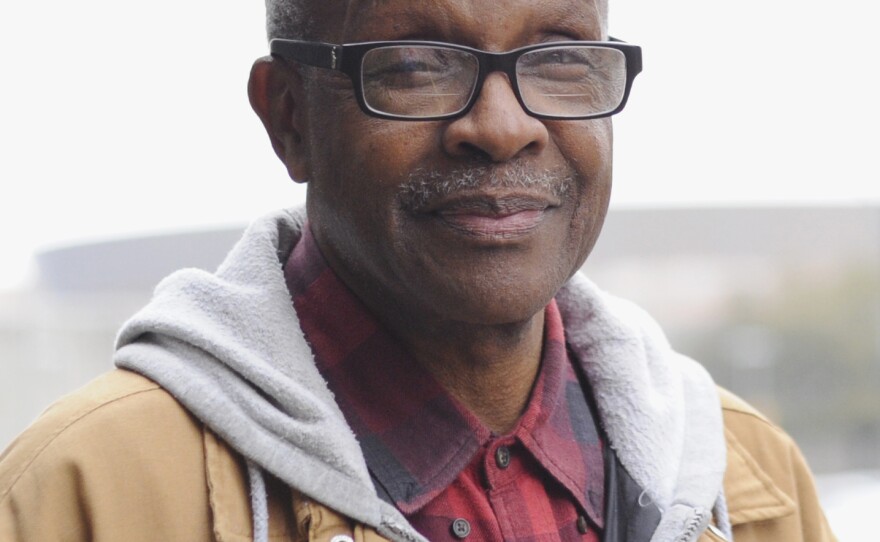

The Deacons for Defense was legally chartered in Jonesboro in 1965, and new chapters began popping up in other communities and states. Bogalusa's chapter was formed that year, and Fletcher Anderson, a Bogalusa native, was part of it.

"The Klan was actually hiding behind the police because the police was protecting them," Anderson says.

According to Anderson, the Bogalusa Deacons started forming after the Klan threatened to bomb Robert Hicks's home. Hicks, a local civil rights leader, was housing two white CORE workers in a black neighborhood.

"They couldn't tell us who could stay in our homes and who couldn't stay in our homes," Anderson says. "We wasn't going to tolerate that kind of life."

At Hicks's home that night, armed community members stood guard against Klan violence. Hicks later filed the lawsuit against the police for harassing civil rights protestors, which led to an injunction. The U.S. Justice Department's legal action helped enforce that injunction. According to Anderson, this helped curb Klan violence in Washington Parish.

"Once they [the Klan] had the police couldn't protect them, then they had to show they own face, and that kind of quieted things down too," he says.

When the police did their job, the Deacons could start backing off.

Anderson is 76 years old. His hands are callused from years of working, primarily at the Crown Zellerbach paper mill in Bogalusa.

"The Klan burned a cross in my yard, and that was because of the activities I use to do at work," Anderson says. "You know, I was probably the first one to be drinking out of the white fountains and going into the white bathrooms and shower, stuff like that. And I guess I was just a target for 'em."

Back in Jonesboro, Charlie White becomes silent when he says hopefully those days are gone.

"I don't think I can go through them again," White says.

White and Anderson may not be organizing patrols or guarding protestors anymore, but they're still Deacons.

"It was all about helping people in the beginning to make things better than what they've been, and making life better for those that been deprived," Anderson says. "That's our job. It going to continue to be our job until we die."